Events

2025/2026

Rebecca Wallbank'On Aesthetic Skepticism and Epistemic Permissivism'

-

Abstract

Many find the prospect of aesthetic skepticism so deeply unappealing that any analysis that implies it is automatically regarded as flawed. Frank Sibley has gone so far as to describe the ‘theoretical sceptic’s doubt as absurd’ (1968: 50–51). I argue we should take aesthetic skepticism more seriously- standard approaches to it fail.

I also argue that there are reasons why we might not be too concerned by the failure of standard approaches. There are two plausible means of dispelling the force of the skeptical concern. The first is to simply reject different premises of the skeptical argument to that which is standard. The second is to accept the skeptical argument but reject the idea that it entails has particularly troubling implications. I lean towards embracing the second. The skeptical conclusion is generally found to be intuitively unappealing in virtue of its association with particular doxastic norms – in particular, those pertaining to the suspension of belief. This paper will argue that such norms are invalid in this particular context.

Adriana Clavel-Vazquez'Towards a Decolonial Universalism in Aesthetics'

-

Abstract

Universalist views of aesthetic value argue that aesthetic judgements make a claim on all aesthetic agents to partake in the invitation to appreciate the relevant objects. Recently, however, universalism has been abandoned in favour of communitarian views, according to which aesthetic judgements only make a claim on specific aesthetic communities. The main advantage of communitarianism is that it can make sense of the role particular interests play in aesthetic valuing. Universalism, on the contrary, has traditionally involved a hegemony that leads to aesthetic marginalization and results in aesthetic injustices. In this paper, however, I argue that communitarian views cannot do justice to the interests of marginalized aesthetic communities because they ultimately involve the surrender of the responsibility of aesthetic agents to partake in a process of mutual recognition. Instead, following insights from decolonial feminists Serene Khader and María Lugones, I argue for a decolonial universalism in aesthetics that takes as a starting point a rehabilitated notion of aesthetic autonomy. By embracing the situated character of aesthetic objects but retaining the idea that they are appreciated for their own sake, aesthetic autonomy can provide the grounds for the universal claim of aesthetic judgements.

2024/2025

Daisy Dixon'Aesthetic Slurs'

-

Abstract

I present a novel account of what I call the ‘aesthetic slur’. Inspired by Patricia Hill Collins’s notion of ‘controlling images’, I delineate images which behave in much the same way as linguistic slurs, analysing particularly their feature of ‘effluence’; how their harmful content can leak out and not be insulated by intention or context. I then use this analysis to explain what went wrong with Makode Linde's controversial artwork Painful Cake (2012).

Content warnings: racist & antisemitic imagery and language.

Vid Simoniti'The Cognitive Value of Inconclusivity in Art'

-

Abstract

Arguments have conclusions, but artworks rarely do: more often, artworks leave us in a state of rumination, perplexity or musing. Here I defend the idea that such art is epistemically valuable, insofar as it allows subjects to entertain propositions, which they are not yet in a position to know. The fact that we are drawn to inconclusive states of pensiveness in artworks suggests that human agents are, in some sense, irredeemably epistemically flawed, capable of only imperfect epistemic access to some aspects of reality. To illustrate this fallen epistemic state further, I draw on Cora Diamond’s concept of the ‘difficulty of reality’ and Hannah Arendt’s analysis of thinking.

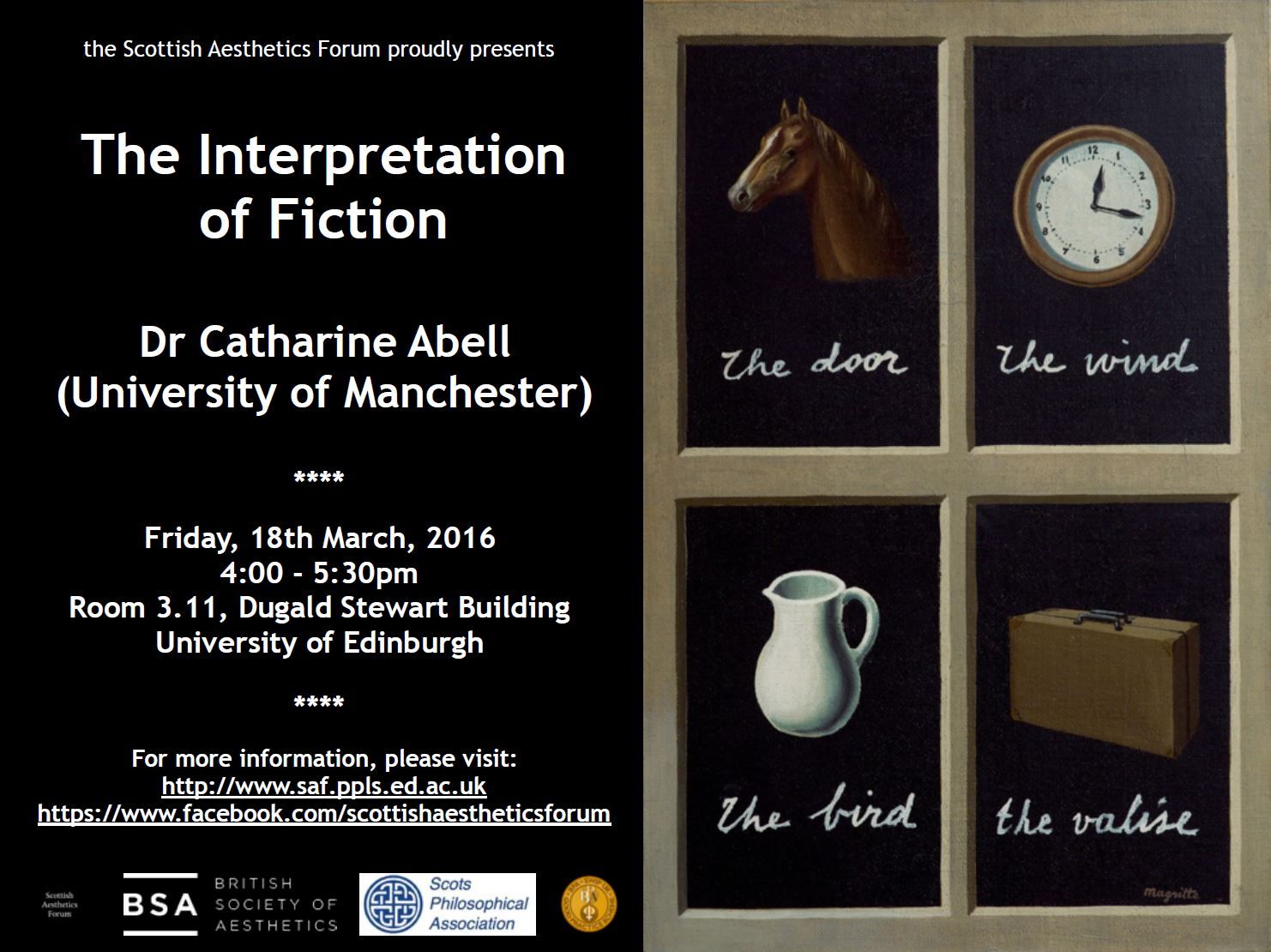

Catharine Abell

-

Abstract

This paper concerns the epistemology of art appreciation. Some argue that the aesthetic appreciation of an artwork requires first-hand experience of it or of a suitable reproduction of it. However, some descriptions of avant-garde and contemporary artworks seem capable of putting us in a position to appreciate them. Either the appreciation of such artworks is not aesthetic, or first-hand experience is not always necessary for aesthetic appreciation. I will remain neutral regarding whether or not the appreciation of such artworks is aesthetic. Instead, I will try to identify some epistemic constraints on art appreciation that apply both to those works we can appreciate via descriptions of them and to those works the appreciation of which seems to require first-hand experience.

Irene Martínez Marín

-

Abstract

Being rational requires mental coherence, which consists in satisfying distinctive requirements that prohibit certain combinations of attitudes. While philosophers debate the normative significance of coherence requirements in the practical and theoretical domains, they have largely neglected parallel questions in aesthetics. This paper examines the normative relationship between two central aesthetic attitudes: aesthetic judgement and aesthetic liking.

I distinguish between two forms of intrapersonal aesthetic coherence: taste consistency and attitudinal coherence. Prominent accounts have defended taste consistency, claiming it prevents identity fragmentation (Cohen, 1998) and enables the development of personal style (Riggle, 2015). Against this view, some have argued that consistency is to be located among an agent’s ethical beliefs about art’s value and function, rather than among their aesthetic preferences (John, 2023). While it is promising to locate aesthetic coherence at an attitudinal level, I contend that there is nothing distinctively aesthetic about this form of coherence or its normativity, as belief-consistency applies to all kinds of beliefs.

I propose that aesthetic coherence is better understood as a form of local coherence between aesthetic judgement and aesthetic liking. When agents fail to align these attitudes—either by disliking something judged aesthetically valuable or liking something judged to lack aesthetic merit—they may violate a duty of respect for aesthetic value. More controversially, I suggest that violating this coherence requirement demonstrates a lack of self-respect. I conclude that we have a normative demand to align our aesthetic judgements and likings, as this form of coherence is intrinsically connected to aesthetic value.

Luvell Anderson

-

Abstract

Effective satire ruffles feathers: It disrupts commonplace prejudices by deftly presenting an alternative frame of the ideas taken for granted, often irreverently. This irreverence poses a danger for the racial satirist who must attack those prejudices. Is racial satire possible in our current era? Do satire’s linguistic mechanisms ensure its irreverent critique is ethically good? In this talk, I discuss these challenges and offer thoughts about how we might navigate them.

Jennifer Welchman

-

Abstract

Docudramas are historical fiction films whose plots revolve around real events. Some docudramas, also known as biopics, focus upon events in the lives of real people. Film theorist Jim Welsh has characterized these films as “a mendacious genre” of “movies that exist mainly to tell entertaining lies.” The Imitation Game is a case in point; a highly successful biopic that fact-checking reviewers roundly condemned for its many historical inaccuracies. Should we care and, if so, why? Do historical inaccuracies undermine the aesthetic value of docudramas like The Imitation Game?

Chris Earley

-

Abstract

Within the philosophy of art, cognitivists aim to answer two questions: 1) how do artworks improve our epistemic standing? 2) does an artwork’s cognitive value contribute to its value qua art? Over recent years, cognitivists have had much success in answering these two questions. However, in this presentation I will argue that cognitivists routinely overlook an important factor relevant to explaining how we learn from art. Taking my cue from recent work in social epistemology, I propose that cognitivists should pay closer attention to how the epistemic and social norms cultivated within artworlds help or hinder our ability to learn from and appreciate art. However, I will argue that once we turn our attention to this, we find that artworlds are unlike other kinds of epistemic communities. Rather than cultivate the normative stability – or ‘epistemic discipline’ – that other domains of inquiry take to be central to explaining their epistemic successes, artworlds appear to cultivate precisely the opposite. Artists are encouraged to break norms and to explore weird, demanding, and opaque approaches to inquiry. I contend this opens up a new front for debate between cognitivists and anti-cognitivists over the epistemic opportunities and hazards offered by being undisciplined.

Emily Caddick Bourne

-

Abstract

Mark Windsor has recently developed an account of the aesthetic experience of the uncanny which links it to the subject's uncertainty concerning the natural and the supernatural. I will suggest an alternative view, with the aim of showing why unwavering commitment to naturalistic beliefs does not detract from engagement with the uncanny. I propose that the experience involves attending to a particular kind of explanatory incongruity, plus, often, engaging in fiction-making which allows us to manage and modulate that experience of incongruity. This account illuminates some performances and artefacts which invoke ideas of the supernatural whilst using documentary techniques and/or face-to-face encounters with performers or locations. As examples, I will consider: some instances of 'paranormal' photography; the affinity between ventriloquism and the uncanny; the attraction of touring 'haunted' places, and the application of the concept of 'kayfabe' to some magic and mentalism performances. The account I'll develop has some further implications for the role of familiarity with folklore in the aesthetic experience of nature, and it clarifies the relationship between debunking and aesthetic appreciation.

This talk is part of my ongoing work with Craig Bourne (University of Hertfordshire) on the aesthetic experience of the extraordinary.

Nathan Wildman

-

Abstract

Arguably, the most significant development in modern aesthetics is the ready availability of increasingly powerful computing technology. Said technology not only provides artists with new tools & methods for approaching familiar artistic forms but also potentially supports the development of new art forms. And while recent years have seen a dramatic uptick of philosophical interest here, there is still a great deal of work to be done when it comes to understanding digital art.

My aim in this talk is to make some progress in this area by exploring the aesthetic potential of Augmented and Virtual Reality (AR & VR). After spelling out some background notions, I begin by first examining the idea that digital tools allow for the remediation of existing art forms (Lopes 2009). With this in place, I pivot to focus on AR/VR as digital mediums. Specifically, I detail how both engender the broad remediation of non-virtual art forms, including cinema, theatre, and visual art. This leads to a further question: are AR and VR only good for remediating existing art forms, or do they allow us to produce genuinely novel art kinds? Put another way, we can ask, are AR and VR just 'old wine in new bottles' when it comes to art-making possibilities?

The remainder of the talks makes the case that both AR and VR in fact support novel art forms. First, considering VR, I use the example of what I call "plunge paintings", an art form consisting of visual artworks the appreciation of which requires viewers virtually “plunge” themselves into. Such an art form is, I contend, not possibly realized in physical reality; consequently, it is something that could only be realized via the VR medium. Second, with regards to AR, I describe “dual engagement” works, where appreciators are required to simultaneously engage with a single artwork both in and outside of AR at the same time; the result is a work that has incompatible (virtual and physical) features. So understood, the resulting art form is not realizable in any purely physical medium, ensuring that it is also genuinely novel.

After briefly discussing how we might go about developing a language and criteria for aesthetically appreciating these new art forms, I conclude by gesturing towards other possible avenues artists might pursue while limning the aesthetic potential of AR & VR.

2022/2023

-

Abstract

Joint work with Daniel Stoljar

The paradox of fiction is a puzzle concerning why we respond emotionally to fiction, given that we know the objects of fiction are not real, and the events in fiction do not occur. In this paper we offer a novel account of how fiction engages the imagination that explains why we respond as we do, and in doing so we provide a novel solution the paradox. The key to our solution is the recognition that the authors of fiction do not only instruct us to imagine that certain things are the case, but they also instruct us to imagine what various objects and events are like to people of various kinds or with various perspectives. In complying with their instructions, we often imagine what various events feel like to those people—we have vicarious experiences—and so go into imaginative states that are phenomenally similar to the experiences of the subjects from whose perspectives we are asked to imagine. Given that such experiences are exactly what authors have instructed us to undertake, the affective responses that they involve are perfectly rational.

-

Abstract

Virtual artworks (videogames, VR pieces, augmented reality pieces, etc.) are subject to what I call cognitive pessimism. Approximately, cognitive pessimism holds that certain art-kinds (in this case, virtual art) put audiences in cognitively vulnerable positions, and can be devalued as art accordingly. In this talk, I argue that virtual artworks do not necessarily put their users in cognitively unfavorable positions. This claim might strike you as banal and obvious, but I will argue that its success has interesting consequences for art-criticism broadly. This talk will be divided into three sections. The first section argues that cognitive pessimism is a philosophically defensible position and can be articulated without the use of causal language. Specifically, cognitive pessimism in its most persuasive form holds that properly appreciating virtual artworks requires a pernicious shift in our sub-doxastic attitudes. The second section argues that this position fails on two grounds: that this shift in sub-doxastic attitudes might not be required to appreciate all virtual artworks, and that this shift can be the site of cognitive value. The final section argues that the failure of cognitive pessimism might be reason for art critics to be more attentive to the potential cognitive effects of individual artworks.

2021/2022

-

Abstract

In this presentation I will make the claim that bodies can be ethical in the sense that they can both express ethical attitudes and can serve as the site of ethical benefit or harm – of care or of abuse. First, I’ll start by showing how philosophers such as Plato and Kant have privileged Reason and a good will over bodily forms of ethical action. Next, I’ll discuss one or more theories of communication in art, such as that of R.G. Collingwood, where words are considered necessary in order to know what we are thinking. Here I’ll show how in our legalistic and contractarian society we are also bound by our words, as promises, as intentions, to bind us to action, and to express consent for joint action. After that, I’ll show how there is, however, evidence to show that we can both know and express without words. Indeed, some psychologists and philosophers of mind, such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Shaun Gallagher, and others, have held that forefront consciousness and verbal expression is the LAST part of the thought chain. What we can put into words, then, might just be the partial wisdom of the last-to-know in the chain of thinking and knowledge events. Finally, I’ll support these claims with evidence from dance practitioners and scholars who have noticed that bodily attunement and awareness provide a fruitful way to care for ourselves as well as others. These include somatic movement experts as well as specialists in community dance and disability.

-

Abstract

Starting from the Predictive Processing framework, I will explore a few of the many reasons that an agent built to minimize uncertainty might be attracted to horrifying and highly uncertain materials (e.g. books, movies, games, etc.). The answer turns out to be complex - with some forms of attraction leading to significant benefits for predictive agents like us, while others are less adaptive and even potentially dangerous. Casting a light on the computational mechanisms underlying our experience of, and attraction to, horror can help tease apart these varying modes of attraction, and so help us better understand the value and dangers of horror.

-

Abstract

Against Philocles’s initial scepticism, against his ongoing fear of the dangers, and completely against fashion, under the sagacious guidance of Theocles, Philocles becomes a ‘lover.’ Philocles’s retelling of his conversion from moderate sceptic to philosophical enthusiast—a passionate lover of true nature—forms the central narrative of Shaftesbury’s The Moralists: A Philosophical Rhapsody. Philocles’s story climaxes with him observing the most philosophical experience, that is, the sublime. Philosophical aestheticians typically read Shaftesbury here only in anticipation of the modern concept of the aesthetic sublime; that is, as a transporting affect of grand and threatening (physical) nature. However, I argue that this captures just a small part of Shaftesbury’s understanding of the sublime and its role in his philosophical project. In this talk, I take a broader view of Shaftesbury’s sublime as a creative philosophical practice, an art of love. Exploring how, like Philocles, we might all become true lovers.

-

Abstract

In what ways does the use of AI image-making technology impact upon human creativity? On the one hand, it has made creative expression more accessible to a wider range of people. In the realm of photography for instance, thanks to the development of a range of editing features made possible by AI, human agents are able to access a larger range of tools with which to express themselves through aesthetic means. Meanwhile, platforms are being developed for artists who are unfamiliar with the increasingly complex world of algorithms and programming, to engage with machine learning and generative image-making processes. However, as many theorists have highlighted, there is the risk that, with the increased automation of the processes of aesthetic creation and aesthetic choices, values become increasingly homogenised and, accordingly, aesthetic diversity decreases. To assess how increases in automation and rule-based production processes impact upon human creativity, I examine the role of constraints in creative practice.

-

Abstract

Modern buildings do not easily harmonize with other buildings, regardless of whether the latter are themselves modern. This often-observed fact so far has not received a satisfactory explanation. To improve on existing explanations, this paper first generalizes an observation of Ortega Y Gasset’s concerning modern fine art, and then develops a metaphysics of styles that is inspired by work in the philosophy of biology. The resulting explanation is that modern architecture is incapable of developing patterns that facilitate harmonizing, because such patterns would humanize buildings, while modern architecture is a homeostatic property cluster with a dehumanizing motive at its core.

- Abstract

I consider what draws us to perceiving beautiful bodies in art and athletics--repeatedly and over time--that is informed by viewers' changing perceptions derived from recent publications in fashion and sport, the philosophy of sport, feminist film theory and aesthetics under the ever-expanding umbrella of somaesthetics.

The essay is forthcoming in Andrew Edgar & William Morgan (eds.), Somaesthetics and Sport (Brill Press).

2020/2021

- Abstract

Charles Rennie Mackintosh is still a key figure in the aesthetic culture that developed from a rationalist poetics within the Art Nouveau Movement. From a young age, Mackintosh approached the world of art, design, and architecture through a keen sensibility, capable of bringing the reflections of Arts & Crafts to bear on the world of interiors, buildings and artefacts. It means that his artistic approach to the spatial dimension makes his work an illustrious lesson in an ethic of creativity based on profound freedom of expression. Mackintosh's culture developed in a vibrant historical context and Glasgow at the height of industrial development. The passage from the naturalistic approach to the sensitive reality to the representation of architecture as a synthesis of a series of artistic operations makes Mackintosh emblematic of aesthetic culture.

In this lecture, we would like to illustrate the fundamental stages of the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and, through them, tell the profound aesthetic changes that marked his work in a culture of design, furniture, and mainly interior architecture. His conception of a room or even a house as an artifact has changed from the twentieth century onwards, the way of conceiving the project through the correspondence of the decorative arts and vice versa.

- Abstract

The tools of aesthetics can help us to analyze how we attend to representations and incorporate them into narratives. In recent years, I’ve become increasingly interested in using these tools to understand injustice and pursue justice.

In the first few years after the 2013 founding of the Black Lives Matter movement, videos of racialized police violence circulated widely and raised the profile of Black, Latina/-o/-x and Indigenous communities’ longstanding concerns. However, consequences for the officers who committed acts of violence clearly caught on video were scant. I offer an aesthetic analysis of the cultural training whereby non-expert audiences are taught by authority figures how to interpret these videos and incorporate them into hegemonic narratives designed to exonerate the officers.

I then turn to the current situation. A much larger segment of the white population now acknowledges that racialized police violence is a problem, and individual officers are more likely to face consequences. A large international movement recognized the injustice attending the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the failure to charge the killers of Ahmaud Arbery, and some cities have moved to reduce police funding and change the scope of police activity. However, at the time of this writing the momentum of the movement has slowed and the prospects for deep change are dubious. I will offer an aesthetic analysis of the resistance to hegemonic narratives that lays the groundwork for change, and the processes by which hegemonic narratives reestablish themselves in the public consciousness.

- Abstract

This talk addresses the aesthetic appeal of impossible figures such as the so-called Penrose Triangle (first discovered by the Swedish artist Oscar Reutersvärd) and the impossible stairs that feature famously in M. C. Escher's Ascending and Descending. My interest is why we find impossible figures so visually compelling. Mathematicians and logicians have studied them for their mathematical and logical properties (Mortensen 2010), psychologists for what they reveal about the visual system (Gregory 1997, chap. 10), and philosophers in part for what they tell us about the limits of the imagination (Elpidorou 2016, 11), but we value them mainly as things to look at. This is what I want to understand. I will work in three stages. First, I will define the domain of investigation. What exactly is an impossible figure? Second, I will ask about the experience of looking at impossible figures. Finally, I will appeal to results from experimental psychology to develop an empirically-grounded hypothesis about the visual appeal of impossible figures. If things go well, we will learn something not only about impossible figures, but about ourselves, and how and why we look at visual art in general.

- Abstract

The question “Can machines create Art?” has been widely discussed in the literature on computational creativity. Due to the variety of conflicting definitions of Art, however, answering this question is notoriously difficult. In this talk, I focus on the less addressed question of why humans display opposition to the diffusion of AI systems in the creative sector. To this end, I discuss the results of a survey designed to explore how contemporary audiences perceive the role and value of AI in the context of artistic creativity. I suggest that the discontent against AI art cannot be explained by the fact that machines lack features that are deemed essential for creativity. Rather, I tentatively propose that, no matter how much they approximate these features, it is impossible for machine art to be truly appreciated by humans due to the innate anthropomorphization of the concept of Art itself.

- Abstract

What kinds of issues does the climate emergency present to philosophical aesthetics, and how is the field challenged to respond? I argue that a new research agenda is needed for aesthetics and, to this end, I outline a set of foundational issues which are especially pressing: (1) attention to environments that have been neglected by philosophers, for example, the cryosphere and aerosphere; (2) negative aesthetics of environment, in order to grasp aesthetic experiences, meanings, and dis/values in light of the catastrophic effects of global climate change; (3) bringing intergenerational thinking into aesthetics through concepts of temporality and ‘future aesthetics’; (4) understanding the relationship between aesthetic and ethical values as they arise in nature-society interactions. These issues are by no means exhaustive but they serve as my focus in this talk.

2019/2020

- Abstract

What I call the ‘Ethical Question’ asks whether an artwork’s moral (dis)value ever makes a difference to its aesthetic value. The question, I argue, is ambiguous between an uninteresting, trivial version and an interesting but very hard version. Devastatingly, the literature on the Ethical Question has, I argue, almost exclusively addressed the easy question. In this talk, I’ll explain this ambiguity and then try to see if there is some subset of ways to, as it were, address the trivial question while avoiding triviality. In addition to value theorists, the talk might be of particular interest to those working on such issues as mental causation, metaphysical dependence, explanation, properties, and related issues.

- Abstract

How well do aesthetic concepts like beauty, elegance, harmony, the sublime, and art hold up under critical scrutiny? Do these concepts have any defects that philosophy might be able to diagnose? I'll argue that under natural assumptions, some of these concepts are defective. Moreover we can explore some of the options for replacing the problematic aesthetic concepts with ones that are free of the defects.

2018/2019

- Abstract

What is it to say that something is beautiful? I attempt an answer by arguing against two rival answers. One is aesthetic hedonism, which answers that to say that something is beautiful is to say that it is valuable because pleasurable. I argue against aesthetic hedonism on the grounds that it is incompatible with the care we take to make accurate judgments of beauty. The other rival is aesthetic subjectivism, which answers that to say that something is beautiful is to do something other than ascribe to it an objective property. I argue against aesthetic subjectivism on the grounds that it is incompatible with our willingness to act on reliable testimony that something is beautiful. The answer I then propose holds that to say that something is beautiful is to ascribe to it an objective property, whose presence we have reason to judge accurately, since we otherwise risk failing to act as we aesthetically ought.

- Abstract

I offer a set of sufficient conditions for beauty, drawing on Parsons and Carlson’s account of ‘functional beauty’. First, I argue that Parsons and Carlson’s account falls short of adequately delivering on its promise of bringing comprehensiveness and unity to aesthetics, whilst facing a range of counterexamples. Instead, I propose, the account should be modified so as to state that if an object is well-formed for its function(s) and pleases competent judges insofar as it is thus experienced, then it is beautiful. I argue that this version of functional beauty offers greater informativeness, comprehensiveness and unity––accounting for, inter alia, talk of mathematical, literary, and moral beauty. Before concluding, I address a number of objections by way of demonstrating that my proposal survives reflective scrutiny.

- Abstract

Advocates of the ethical criticism of art claim that an artwork’s ethical defects have an impact on its aesthetic value. The ethical critic is interested in the ethical evaluation of a work’s intrinsic features, to see how its ethical value interacts with its aesthetic value. This paper examines the legitimacy of an intrinsic ethical assessment of works of fiction by questioning what should be regarded as a work’s intrinsic ethical defects. I propose a distinction between fictional and actual immorality in fiction that has important consequences for whether the counter-moral content of fictional narratives can be regarded as an intrinsic moral flaw. I argue that we cannot properly speak of a work’s intrinsic ethical demerits, and that thus we can only aspire to an extrinsic ethical assessment of a narrative that depends entirely on contextual considerations: some features of works of fiction can be regarded as ethically significant in certain contexts. Because the ethical assessment can only be extrinsic and context dependent, I conclude that we should defend Contextual Autonomism.

- Abstract

Along with the rich history of adaptation of novels into films, there are numerous examples of films that adapt works of prose non-fiction: Jane Campion’s An Angel at My Table, based on Janet Frame’s autobiographies; Alan Parker’s adaptation of Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, James Marsh’s The Theory of Everything from Jane Hawking’s Travelling to Infinity; Walter Salles’ film of Che Guevara’s The Motorcycle Diaries, and Bennett Miller’s and Adam McKay’s films, respectively, of Michael Lewis’s Moneyball and The Big Short. I will discuss some linked questions about such adaptive relationships. First, it seems obvious, or pretty obvious, that the films are all works of fiction. They are not, for instance, documentary films. So, the first question concerns why that is and whether there is a conception of fiction that makes this clear. Second, is there something we might call ‘the experience of fiction’ that can float free of the actual requirements for fiction? In general I will reflect on what seems to be a process of fictionalisation manifest within these adaptations.

- Abstract

In the eighteenth century, there was an upsurge in philosophical interest in the arts and aesthetic values such as beauty. Indeed with this upsurge of interest came a redefinition of art: by contrast to the prior European tradition, which had defined art as imitation, for eighteenth-century thinkers beauty (not imitation) is the primary, defining purpose of art. In this paper, I discuss a marvellous, but little-known, posthumously published essay by Adam Smith, “Of the Nature of that Imitation which takes place in what are called The Imitative Arts.” I argue that Smith in this essay explicitly contributes to this conceptual transformation in a way tacitly called for, but not elsewhere accomplished by his colleagues: Smith reinterprets artistic imitation itself as a form of “beauty.”

- Abstract

Discussions of the cognitive value of fictional literature usually take for granted that we can learn ordinary facts from fiction, and focus instead on other forms of knowledge or cognitive improvement. I argue that at least some of these other kinds of cognitive value — such as learning ‘what it’s like’ to have different experiences, or acquiring psychological insight into other human beings — presuppose a basis in fact. I outline an account of the conditions under which we learn facts from fiction, and deploy it to better understand how fictions may be sources of other forms of cognitive value.

- Abstract

Impossible colours are mixtures of hues that do not appear on the colour wheel. They are widely taken to be impossible to mix, experience or even imagine. This paper draws on art and science to explore the idea that in fact painters can and do ‘paint’ with impossible colours.

- Abstract

There are a number of ongoing debates in aesthetics concerning the nature and scope of aesthetic properties. In this talk, I consider how these debates might intersect with an important (but philosophically neglected) claim within various religious traditions; that God is perfectly beautiful. In particular, I ask whether we can reconcile this claim with the influential view that aesthetic properties (and their bearers) must be perceptible.

2017/2018

- Abstract

It’s increasingly popular in metaethics to accept a thesis known as Robust Moral Realism (RMR), where RMR is committed, among other things, to a particularly strong form of mind-independence for moral properties, that requires them to be (relevantly) independent of the attitudes of not only actual observers, but ideal observers too. According to RMR, slavery’s wrongness, for example, is not a matter of what anyone, real or ideal, would think about it, or how anyone, real or ideal, would feel about it. RMR can say, then, that slavery would be wrong even if everybody thought it was right, and even if ideal observers (specified in non-moral terms) would think it was right.

Consider an aesthetic counterpart of RMR – what I shall call Robust Aesthetic Realism (RAR). RAR would be committed, analogously, to a particularly strong form of mind-independence for beauty, that requires beauty to be (relevantly) independent of the attitudes of not only actual observers, but ideal observers too. RAR can say that Venice would be beautiful even if everyone thought it was ugly, and even if ideal observers (specified in non-aesthetic terms) would think it was ugly.

It’s striking that while RMR is popular, RAR is not at all popular. Further, most philosophers take robust realism to be more plausible in the moral case than in the aesthetic case. There are two ways that this widespread view about the relative tenability of the two theses could be correct. The first way is what I call Obstacle Asymmetry: RAR faces obstacles that RMR doesn’t face. The second I call Motivation Asymmetry: RMR is better motivated than RAR – there are compelling arguments for RMR that lack counterparts in the aesthetic case.

This paper considers whether Motivation Asymmetry holds. I argue that there is no good reason to think it does. I consider the three main kinds of argument that are commonly taken to supply a motivation for RMR, and I argue that each is no less compelling in the aesthetic case. If I am right, then in the absence of further arguments for RMR, we should take robust realism to be no less motivated in the aesthetic case than in the moral case.

This is a surprising result. Metaethicists often talk as though the considerations that motivate RMR are specifically ethical ones, and as though RAR is not correspondingly well-motivated.

- Abstract

The paper explores how the idea of experience, with primary focus on aesthetic experience, might apply to literature in general and poetry in particular. Any kind of sensory experience seems at best marginal, for example, to the novel. To speak of the experience of a novel seems not to be speaking of sensory experience. Yet the aesthetic—certainly aesthetic experience—seems closely tied to the sensory. Do we then mean something different when talking of experience in the literary realm? Maybe. But poetry lends itself more readily to talk of experience, aesthetic experience in particular and even sensory experience. Is not much of the pleasure of poetry bound up with the sounds, rhythms and textures of poetic language? And is that not both sensory and aesthetic? Although this might seem incontestable it also hints at a kind of formalism in the aesthetic appraisal of poetry. If our focus is on sounds and rhythms what becomes of poetic subject matter? Is that excluded from aesthetic appraisal? That seems undesirable in itself, especially so for those who promote the indivisibility of form and content in poetry. Can form-content unity in a poem afford aesthetic experience? If so, how is that explained? If not, then are we back to a different kind of experience (more like the novel?) in associating poetry with aesthetic experience?

- Abstract

In the course of arguing for her wider and well-known view that pornography literally silences women, Rae Langton suggests that a piece of pornography is, inevitably, a speech act: an act of speaking. In this view, she is accompanied by Ronald Dworkin and by Caroline West (with whom she is a sometime co-author); she also, at least on the face of it, shares the assumption with a dominant interpretation of the US constitution, according to which the First Amendment should protect pornography under the aegis of free speech. On the other side of the debate are those who argue that a piece of pornography is not and cannot be a speech act. These include philosophers such as Jennifer Hornsby, Jennifer Saul and Louise Anthony. One striking thing about this debate that it apparently operates at a level of complete generality: either pornography always is a speech act, or it never is. I will argue that neither of these conclusions is acceptable. In particular, I will draw an instructive comparison with non-pornographic fiction, which in some cases can correctly be said to deliberately convey a message, as speech does, but in other cases clearly does not.

- Abstract

Scientists routinely speak of the aesthetic merit of theories, proofs and explanations, often regarding the experience of beauty and elegance in science as a motivation for their work and an indication of its truth. But aesthetic judgments in science are as controversial as they are widespread. On one side, aestheticians have worried that statements about the beauty of a theory or the elegance of a proof are merely metaphorical and lack genuine aesthetic status. On the other side, philosophers of science have wondered why aesthetic concerns should play any role in the search for scientific knowledge. I address this two-fold challenge by asking how judgments of beauty could be both aesthetic and relevant for scientific enquiry. I propose an answer inspired by the Kantian idea that aesthetic experience is grounded, at least in part, in the subject’s spontaneous intellectual activities. I argue that relevant aesthetic judgments are grounded in the subject’s awareness of her creative intellectual activities in devising and grasping a theory. And I suggest that judgments of this kind may offer a heuristic tool for scientific enquiry by indicating achievements of understanding.

- Abstract

“All epistemology begins in fear”, claim Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison (2007: 372) in the final chapter of their history of objectivity. Their account shows that our relationship with objectivity coincides with the story of the scientific self, and of the epistemic virtues that communities cultivate explicitly to “discipline” their practitioners. In this talk I aim to show that the notion of representation in philosophy of science, and in particular that of mimesis, followed a fate very similar to that of objectivity. Specifically, I claim that the somewhat tormented relationship philosophers of science have developed with mimetic accounts of representation marks just another chapter in the history of epistemic fear.

A widespread criticism of mimetic accounts of representation is that they are merely a “common sense” view, built on the assumption that representation can be exhausted simply by postulating a mirror-like, dyadic relation between a representational source and its target. But as Stephen Halliwell (2002) argued in The Aesthetics of Mimesis, this kind of criticism was far more nuanced even in Plato, credited as one of the earliest and most adamant critics of mimetic accounts of art (and knowledge more broadly). I propose a revival of mimesis in philosophy of science that looks explicitly at texts in aesthetics such as Halliwell’s, to show the unique potentialities this historical concept still holds when it comes to our understanding of scientific representation. Drawing on concrete case-studies, I will propose a positive account of mimesis as historically-located, enactive and iconic. Construed as a form of iconicity, I claim, mimesis can be understood as a fertile representative device to discover, articulate and present new epistemic possibilities.

2015/2016/2017

- Abstract

This paper will consider whether works in genres such as biopics, docudramas, and Shakespeare’s History Plays are fiction or non-fiction. It will argue that (a) some of them are non-fictions and (b) that, for others, it is a mistake to classify them under either heading. This will lead to a consideration of what motivates authors of non-fiction, and argues that a commitment to truth has both an epistemological and a non-epistemological function. Along the way it will conclude (as does Kendall Walton) that it is misguided to think that fiction is more of a philosophical puzzle than non-fiction.

- Abstract

Ordinary testimony transmits knowledge. But aestheticians have been sceptical of whether aethetic testimony transmits aesthetic knowledge. Although the debate in the philosophical literature focuses largely on normative and conceptual questions, empirical claims about folk resistance to aesthetic testimony play a significant role in that debate. Our studies explore folk attitudes towards aesthetic testimony. We argue that experimental results do not support pessimism about the epistemic value of aesthetic testimony.

- Abstract

It is a curious fact about the philosophical literatures on both propaganda and pornography that they tend to talk about these phenomena as if they were primarily linguistic. Yet by far most pornography today is pictorial and most propaganda has a significant pictorial component. This paper aims to shift the focus in the conversations to pictures and begins to think through some of the implications of this shift. In particular, I’ll be developing a peculiarly pictorial model of persuasion that better suits the work that pornography and propaganda can do. Along the way, I’ll use some examples of highly persuasive pictures from the Italian Renaissance.

- Abstract

Julian Dodd has recently argued against what he terms ‘local descriptivism’ as a meta-ontological principle in the philosophy of art. Dodd distinguishes local descriptivism from another meta-ontological view, ‘folk-theoretic modesty.’ The two views differ as to the relationship between the folk-theoretic beliefs about artworks implicit in our practices and the correct ontology of art for particular art forms. The local descriptivist thinks that the folk-theoretic beliefs in some way determine the ontological characters of artworks, whereas proponents of folk-theoretic modesty think that properly rigorous philosophical inquiry in accordance with the demands of “mainstream metaphysics” can lead us to rightly conclude that our folk ontology of art is seriously in error. Dodd takes his objections to descriptivism as counting equally against the idea that the ontology of art is by its very nature constrained by artistic practice. I argue, against Dodd, that according a grounding role to artistic practice in the ontology of art need not conflict with the demands of meta-ontological realism and can allow for both practices and folk beliefs about those practices to be revised. Practice, I argue, must ground our ontological inquiries into the nature of artworks of various kinds because the ontologist’s task is to make sense of the practices into which such artworks enter. But neither the practices themselves nor our folk beliefs about those practices are sacrosanct. In taking ontology of art to be reflectively accountable to artistic practice, I also reject Thomasson’s global descriptivism in the ontology of art. My objection, however, is independent of the merits of Thomasson’s ‘easy view’ in metaphysics more generally. Rather, I argue, she misunderstands the nature of the questions that ontologists of art are asking. Ontology of art is by its very nature reflective and potentially revisionary of certain aspects of our practice. It involves not conceptual analysis but the codification of a practice in a way that clarifies the role played by certain things in that practice.

- Abstract

There are two views of the nature of fictive utterances in the existing literature. According to Searle and others, fictive utterances involve the overt pretense of performing ordinary illocutionary acts, such as assertions. According to Currie, Stock and Davies, they consist in a distinctive kind of illocutionary act, characterised by a communicative intention to elicit imaginings in an audience. I argue against both these views on epistemological grounds. Neither, I argue, is able to explain the fact that readers are, by and large, able to identify the contents of authors’ fictive utterances because both views are unable to accommodate the role of context in interpretation. I defend an alternative view according to which fictive utterances are declarations, illocutionary acts which are distinctive in effecting changes to the status of their objects simply in virtue of their successful performance. I argue that it follows from this view that we should be anti-intentionalists about the contents of fictive utterances. Although authors may competently and intentionally exploit them, conventions, rather than authors’ intentions, determine the contents of the utterances by which works of fiction are produced.

- Abstract

Pictures are surfaces with marks on them. Different kinds of pictures have different kinds of marks, produced in different ways. The marks themselves have an interest in painting and drawing which they do not have in photography and cinema. This difference enables us to identify and explain a feature of some pictures which I call “apparent transparency”. This is not the same as Walton-style transparency and pictures which have apparent transparency need not be (and in my view are not) transparent. The interest that marks have in painting are of different kinds depending on whether those marks are co-incident. I explain the notion of co-incidence and use it to highlight some of the aesthetic differences between different kinds of paintings and to extend Wollheim’s notion of twofoldness.

- Abstract

The arts have an ambivalent status in the history of the sublime. Some philosophers have taken poetry, painting, and music to be sublime, while others have clearly designated the arts as capable only of representing, conveying, or expressing it, that is, somehow derivative of sublimity in nature, whether that be through visual depictions of sublime phenomena, through the language of poetry and literature, or through music. Here, I take as a starting point the eighteenth-century view that the arts, on the whole, are not sublime as such and consider it with reference to recent debates in aesthetics. I argue that (1) paradigm cases of the sublime involve qualities related to overwhelming vastness or power coupled with a strong emotional reaction of excitement and delight tinged with anxiety, and (2) because most works of art lack the combination of these qualities and accompanying responses, they cannot be sublime in the paradigmatic sense. Along the way, I discuss differences between sublimity and profundity in art, as well as considering the inclusion of works of architecture and some forms of land art in the category of the sublime.